Cattle and Buffalo

GUIDELINES FOR HUMANE HANDLING AND TRANSPORT

Increased production through humane treatment of slaughter animals can be achieved, for example, through:

- Reduced carcass damage and waste and higher value due to less bruising and injury;

- Decreased mortality;

- Improved quality of meat by reducing animal stress;

- Increased quality and value of hides and skins.

EFFECTS OF STRESS AND INJURY ON MEAT AND BY-PRODUCT QUALITY

A. MEAT QUALITY

The energy required for muscle activity in the live animal is obtained from sugars (glycogen) in the muscle. In the healthy and well-rested animal, the glycogen content of the muscle is high. After the animal has been slaughtered, the glycogen in the muscle is converted into lactic acid, and the muscle and carcass becomes firm (rigor mortis). This lactic acid is necessary to produce meat, which is tasteful and tender, of good keeping quality and good colour. If the animal is stressed before and during slaughter, the glycogen is used up, and the lactic acid level that develops in the meat after slaughter is reduced. This will have serious adverse effects on meat quality.

Pale Soft Exudative (PSE) meat (Fig. 1)

PSE in pigs is caused by severe, short-term stress just prior to slaughter, the meat becoming very pale with pronounced acidity (pH values of 5.4- 5.6 immediately after slaughter) and poor flavour. This type of meat is difficult to use or cannot be used at all by butchers or meat processors and is wasted in extreme cases. Allowing pigs to rest for one hour prior to slaughter and quiet handling will considerably reduce the risk of PSE.

Dark Firm and Dry (DFD) meat (Fig. 1)

This condition can be found in carcasses of cattle or sheep and sometimes pigs and turkeys soon after slaughter. The carcass meat is darker and drier than normal and has a much firmer texture. The muscle glycogen has been used up during the period of handling, transport and pre-slaughter and as a result, after slaughter, there is little lactic acid production, which results in DFD meat. This meat is of inferior quality as the less pronounced taste and the dark colour is less acceptable to the consumer and has a shorter shelf life due to the abnormally high pH-value of the meat (6.4-6.8). DFD meat means that the carcass was from an animal that was stressed, injured or diseased before being slaughtered

| Fig.1: A. Pale Soft and |

| Exudative (PSE) meat |

| B. Normal meat |

| C. Dark Firm and Dry (DFD) meat |

Spoilage of meat

- It is necessary for animals to be stress and injury free during operations prior to slaughter, so as not to unnecessarily deplete muscle glycogen reserves.

- It is also important for animals to be well rested during the 24-hour period before slaughter.

- This is in order to allow for muscle glycogen to be replaced by the body as much as possible (the exception being pigs, which should travel and be slaughtered as stress free as possible but not rested for a prolonged period prior to slaughter).

- This acid gives meat an ideal pH level, measured after 24 hours after slaughter, of 6.2 or lower. The 24h (or ultimate) pH higher than 6.2 indicates that the animal was stressed, injured or diseased prior to slaughter.

- Lactic acid in the muscle has the effect of retarding the growth of bacteria that have contaminated the carcass during slaughter and dressing.

- These bacteria cause spoilage of the meat during storage, particularly in warmer environments, and the meat develops off-smells, colour changes, rancidity and slime.

- This is spoilage, and these processes decrease the shelf life of meat, thus causing wastage of valuable food.If the contaminating bacteria are those of the food poisoning type, the consumers of the meat become sick, resulting in costly treatment and loss of manpower hours to the national economies.

- Thus, meat from animals, which have suffered from stress or injuries during handling, transport and slaughter, is likely to have a shorter shelf life due to spoilage. This is perhaps the biggest cause for meat wastage during the production processes.

Bruising and injury

Bruising is the escape of blood from damaged blood vessels into the surrounding muscle tissue. This is caused by a physical blow by a stick or stone, animal horn, metal projection or animal fall and can happen anytime during handling, transport, penning or stunning. Bruises can vary in size from mild (approx. 10-cm diameter) and superficial, to large and severe involving whole limbs, carcass portions or even whole carcasses. Meat that is bruised is wasted as it is not suitable for use as food because:

- It is not acceptable to the consumer;

- It cannot be used for processing or manufacture;

- It decomposes and spoils rapidly, as the bloody meat is an ideal medium for growth of contaminating bacteria;

- It must be, for the above reasons, condemned at meat inspection.

Bruising is a common cause of meat wastage and can be significantly reduced by following the recommended correct techniques of handling, transport and slaughter.

Severe bruising – cattle carcass

Injuries such as torn and haemorrhagic muscles and broken bones, caused during handling, transport and penning, considerably reduce the carcass value because the injured parts or in extreme cases the whole carcass cannot be used for food and are condemned. If secondary bacterial infection occurs in those wounds, this causes abscess formation and septicaemia and the entire carcass may have to be condemned.

Severely bruised cattle head and Transport injury

B. Hides and Skins Quality

Hides and skins should have the highest value of any product of slaughter animals, other than the carcass. This is particularly so of cattle hides and small ruminants. Useful leather can be made only from undamaged and properly treated skins. Proper handling of these items is important to produce a valuable commodity. Careless damage to hides and skins will cost the industry much loss.

Hides and skins of slaughter livestock can be damaged by thoughtless handling and treatment of these animals in the following ways:

Hide Damage – Brands and Injury

1. Before Slaughter:

- Indiscriminate branding;

- Injuries from thorns, whips, sticks, barbed wire and horns;

- Unsuitable handling facilities;

- Badly designed and constructed transport vehicles.

2. During Slaughter:

- Causing the animals to become excited and injuring themselves;

- Hitting or forcefully throwing the animal;

- Dragging the carcass along the ground, alive or dead.

Consideration for animal welfare during transport and handling will improve the value of these by-products.

HANDLING OF LIVESTOCK

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

The first principle of animal handling is to avoid getting the animal excited. It takes up to 30 minutes for an animal to calm down and its heart rate to return to be normal after rough handling. Calm animals move more easily and are less likely to bunch and be difficult to remove from a pen. Handlers should move with slow, deliberate movements and refrain from yelling.

Animals may become agitated when they are isolated from others. If an isolated animal becomes agitated, other animals should be put in with it. Electric prodders (prods) should be used as little as possible or only on stubborn animals. However it is more humane and causes less damage to give an animal a mild electric shock than to hit it with a stick or twist its tail. Battery-operated prods are preferred to mains-current operated ones. The voltage used should not exceed 32 V and never be used on sensitive parts such as eyes, muzzle, anus and vulva.

A battery- operated electric prodder

Mains- current operated electric prodder

Instead of prods, other droving aids should be used such as flat straps, rolled-up plastic or newspaper, sticks with flags on or panels (Panels for droving pigs are boards made of solid material, such as wood, plastic etc. of approx. 1-m square which are held by the drover to block the vision and movement of pigs and so guide its direction) for pigs. Hesitant animals can often be enticed into pens or vehicles by first leading in a tame animal and the others will follow.

Flat strap for droving

HANDLING IN CROWD PENS AND RACES

Overloading the crowd pen is one of the most common animal handling mistakes. The crowd pen and the alley that leads to it from the yard should be only half filled. Handlers must also be careful not to force animals to move by using crowd gates. Animals should walk up the race without being forcibly pushed.

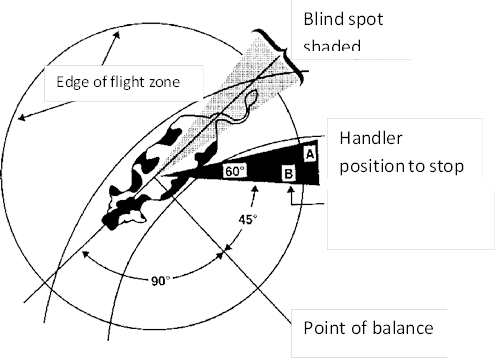

Flight zone and point of balance

An animal’s flight zone is the animal’s safety zone and handlers should work on the edge of the flight zone. If an animal turns and faces a person, the person is outside the flight zone. When a person enters the flight zone, an animal will turn away. If an animal in a pen or race becomes agitated when a person stands too close to them, this indicates that the person is in the flight zone and should move backwards away from them.

The installation of solid sides on races and stunning boxes will help calm animals because they provide a barrier between the animals and people who approach too closely. The flight zone size depends on how wild or tame the animal is. Animals with a flighty temperament will have a larger flight zone. Animals that live in close contact with people have a smaller flight zone than animals that seldom see people. An excited animal will have a larger flight zone than a calm one. A completely tame animal has no flight zone and may be difficult to drive.

Curved cattle race with solid sides

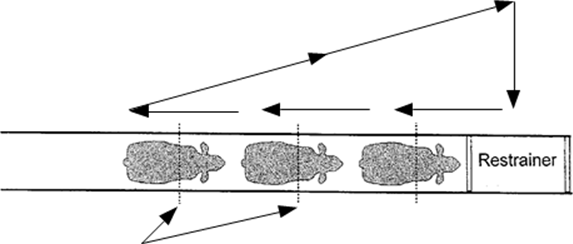

To make an animal move forward, the handler must be behind the point of balance at the shoulder. To get the animal to move backwards, the handler must stand in front of the point of balance. Figure illustrates handler movement patterns, which make it possible to reduce the use of electric prods or goads. Cattle, sheep or pigs will move forward in a race when a handler passes by the animal in the opposite direction of the desired animal movement. The handler must move quickly in order to pass the point of balance at the shoulder to make the animal move forward. The animal will not move forward until the handler passes the shoulder and reaches its hips

Handler movement pattern to keep cattle moving into a squeeze chute or restrainer

Designs of handling facilities

The risk of injury and stress during handling of livestock can be high, causing financial loss to producer, transporter and slaughterhouse. Examples are poorly designed pen fencing, too low or unstable loading ramps, exposure of livestock to heat and intensive sunshine. Properly designed and constructed facilities on farms, at auction yards and slaughter houses etc. will contribute significantly towards the safe handling of livestock, thereby reducing the risk of injuries and stress to animals and workers alike.

Poor designed fencing

Open pens – No shade

Well- constructed pens/platform for offloading and holding cattle

Ramp for pigs and off- loading platform for vehicles leading to holding pens for pigs

Required floor space (m2) per head of livestock for different species

Cattle | Loose | 2.0-2.8 |

Tied | 3.0 | |

Calves or sheep | 0.7 |

Bulls and boars should be individually penned, and if tied, they should be able to lie down. Water must be easily available. Troughs should be high enough or protected to prevent animals from falling in and drowning.

In cold climates, pens should have walls and roofs to protect animals from weather stress. In the tropics, a roof is necessary for holding pens to protect stock, particularly pigs, from heat stroke and sunburn.

Rail distances and heights for different species

Rail distances | Rail height | |

Cattle | 20 cm apart | Top rail 1.5 m high |

Sheep/goat | 15 cm apart | Top rail 0.9 m high |

Pigs | 15 cm apart | Top rail 0.9 m high |

Ostriches | 20 cm apart | Top rail 1.5 m high |

Floors: Pen floors should be non-slip and have a gradient of not more than 1:10. If animals slip, this causes bruises, fractures, dislocations and/or skin damage. Concrete floors should have patterns engraved, or covered in mesh to provide traction, at the same time facilitating cleaning. Failing this flat stone will suffice.

Tubular rails and concrete walls for pen partition, non- slip concrete floor

Non slip concrete pen floor partition

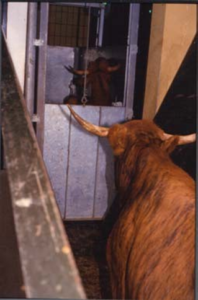

Raceways—Lanes are necessary for animals to walk or be led on/off vehicles and platforms into holding pens or slaughter facilities etc. Races should be narrow enough so that animals cannot turn around or get wedged beside each other. This results in animals becoming injured, if they panic or are manhandled. Race width for cattle should be approximately 76 cm, depending on breed and size.

Raceway for cattle from holding pens to stunning area

One cattle waiting at the end of raceway in front of stunning box, another cattle staying in stunning box

TRANSPORT OF LIVESTOCK

The need to transport food animals occurs essentially in commercial agriculture and to a lesser extent in the rural or subsistence sector. These animals need to be moved for a number of reasons including marketing, slaughter, re-stocking, from drought areas to better grazing and change of ownership. Typically, methods used to move animals are on hoof, by road motor vehicle, by rail, on ship and by air.

Generally the majority of livestock in developing countries are moved by trekking on the hoof, by road and rail. Historically, livestock has been moved on foot, but with increasing urbanisation of the population and commercialisation of animal production, livestock transport by road and rail vehicles has surpassed this.

Transport of livestock is undoubtedly the most stressful and injurious stage in the chain of operations between farm and slaughterhouse and contributes significantly to poor animal welfare and loss of production.

Effects of transport

Poor transportation can have serious deleterious effects on the welfare of livestock and can lead to significant loss of quality and production.

Effects of transport and movement include:

- Stress – leading to DFD beef and PSE pork

- Bruising – perhaps the most insidious and significant production waste in the meat industry

- Trampling – this occurs when animals go down due to slippery floors or overcrowding

- Suffocation – this usually follows on trampling

- Heart failure – occurs mostly in pigs when overfed prior to loading and transportation;

- Heat stroke – pigs are susceptible to high environment temperatures and humidity;

- Sun burn – exposure to sun affects pigs seriously;

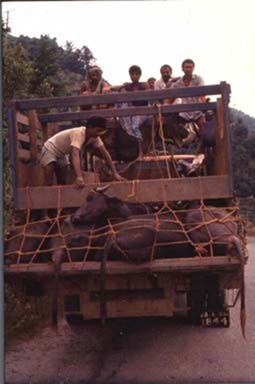

- Bloat – restraining ruminants or tying their feet without turning them will cause this;

- Poisoning – animals can die from plant poisoning during trekking on hoof;

- Predation – unguarded animals moving on the hoof may be attacked;

- Dehydration – animals subject to long distance travel without proper watering will suffer weight loss and may die;

- Exhaustion – may occur for many reasons including heavily pregnant animals or weaklings;

- Injuries – broken legs, horns

- Fighting – this occurs mostly when a vehicle loaded with pig stops, or amongst horned and polled cattle.

Methods of Transport

Cattle The most appropriate methods of moving cattle are on hoof, by road motor vehicle or by rail wagon. Moving cattle on the hoof (trekking) (Fig. 28) is suitable only where road and rail infrastructure does not exist, or when distances from farm to destination are short. This method is slow and fraught with risks to the welfare and value of the animals. Rail transport is useful for short-haul journeys where loading ramps are available at railheads and communication is direct to destination. Road motor transport is by far the most versatile, the method of first choice and the most user friendly.

The most satisfactory method of transporting cattle is by road motor vehicle (Fig. 29, 30). Moving by rail truck (Fig. 31) requires more careful management and trekking is satisfactory for well-planned distances.

Moving cattle on the hoof

Road motor vehicle for transporting cattle (cross slating of cattle truck floor to prevent slipping)

Large truck for cattle transport at unloading platform

Rail truck for transporting cattle

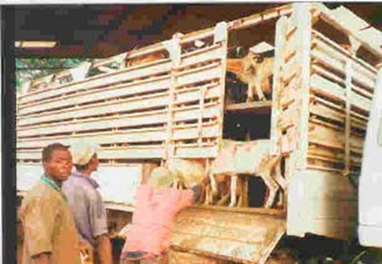

Sheep/goats Of the food animals these are the easiest to transport and generally travel well on hoof, rail or road. Double-deck trucks are also suitable.

Double- deck truck for transporting sheep/goats

Sheep/goats Of the food animals these are the easiest to transport and generally travel well on hoof, rail or road. Double-deck trucks are also suitable.

Double- deck truck for transporting sheep/goats

Types of Vehicles

Any vehicle used for the transport of slaughter livestock should have adequate ventilation, have a non-slip floor with proper drainage and provide protection from the sun and rain, particularly for pigs. The surfaces of the sides should be smooth and there should be no protrusions or sharp edges. No vehicle should be totally enclosed.

Ventilation—Transport vehicles should never be totally enclosed, as lack of ventilation will cause undue stress and even suffocation, particularly if the weather is hot. Poor ventilation may cause accumulation of exhaust fumes in road vehicles with subsequent poisoning. Pigs are particularly susceptible to excessive heat, poor air circulation, high humidity and respiratory stress. Well- ventilated vehicles are necessary. The free flow of air at floor level is important to facilitate removal of ammonia from the urine.

Well- ventilated truck for transporting pigs. Heat combined with hot sun would require a cover (roof) for the vehicle.

Floors—Non-slip floors in all vehicles are necessary to reduce the risk of animals falling. A grid of cross slating made from wood or metal is suitable. The grid can be removable, so the vehicle can be used for other purposes. Other forms of non-slip surfaces such as grass or sawdust are not suitable. Additional balance for animals is provided by partitioning the interior of the vehicle with either wood or metal poles or solid boards. Broken floors will cause leg and other injuries. Vehicle floors should be level with off-loading platforms, otherwise animals will injure themselves climbing off or be manhandled in order to remove them.

Floor space—Livestock require sufficient floor space so that they can stand comfortably without being overcrowded. Overloading results in injuries or even death of livestock.

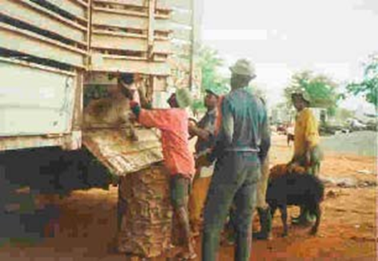

Cattle leg protruding through broken truck floor

Poor offloading facilities resulting in injuries from mishandling of animals

Overloading truck with goats

Goats being trampled in the back of a truck

Overloading truck with water buffaloes

Approximate floor space for transporting different classes of animals

| Classes of stock | Floor area /animal (m2) | |

| Mature cattle | 1.0 – 1.4 * | |

| Small calves | 0.3 | |

| porker | 0.3 | |

| Pigs | baconer | 0.4 |

| sow/boar | 0.8 | |

| Sheep/goats | 0.4 | |

| Ostriches | 0.8 | |

*50-60cm vehicle length/head loaded cross-wise

Allowances should be made for breed and body size. If the floor area is too large for the number of animals, partitions should be used to avoid animals being thrown about.

Sides—The sides of vehicles should be high enough to prevent animals, particularly pigs, from jumping out and injuring themselves. Insides could also be padded at hip level with, for example, old tyres to reduce bruising of cattle and ostriches. Also there should be no gaps through which a leg might protrude and be broken. Narrow entry doors can lead to considerable bruising of hips. Rail trucks should be fitted with spring coupling to cushion jerky movement.

Roof—A roof is not necessary on a transport vehicle for bovines and small ruminants provided the animals are not exposed for hours in the hot sun. Vehicles for pigs should have roofs unless the pigs are to be transported in the early morning or late evening. Poultry should be protected from sun and rain. Transporting in cages or crates will protect them from physical injury. They should be large enough to allow all the birds to sit down and move their heads freely. Ventilation should be adequate.

At the small-scale level in more primitive conditions animals are often transported under very unsuitable conditions, which may cause a great deal of pain or even death through suffocating, heat stress, dehydration etc.

Pre-loading Precautions

There are a number of simple procedures that can be implemented prior to the loading of livestock, which will considerably reduce the risk of injury and stress.

- Pre-mixing of cattle or pigs leads to greater familiarity and these animals travel better than animals that are strangers. Cattle should be mixed in a pen 24 hours before loading. Victimised or wild animals can be weeded out during this period. Fighting amongst pigs that are strangers is common, resulting in skin damage, wounds and stress. Mix pigs from different pens together before loading, smearing pigs with litter or excreta from the same pen so that they smell similar.

- Most animals can be fed and watered before transporting. This has a settling effect. However pigs should not be fed before transport as the feed ferments and the gas causes pressure on the heart in the thoracic cavity, leading to heart failure and death.

- Do not mix horned and hornless animals in the vehicles as this causes bruising and injury. Different species should also not be mixed – sheep, goats and calves under 6 months can be mixed and individual animals can be transported in a loose sack tied at the animal’s neck. Feet should not be tied, and animals should be turned every 30 minutes or so. Bulls should not be carried together with other stock unless separated by a strong partition.

- Animals that are diseased, injured, emaciated or heavily pregnant should not be transported, and unfit, heavy, penfed animals should not travel far as they cannot stand up to the rigours of transport.

- Vehicles should be fitted with a portable ramp to facilitate emergency offloading in case of prolonged breakdowns.

Transport Operations

A number of factors must be taken into account during the journey in order that the animals do not suffer, become injured or die.

Trekking—Only cattle, sheep and goats can be successfully moved on hoof, and here certain risks are involved. The journey should be planned, paying attention to the distance to be travelled, opportunities for grazing, watering and overnight rest. Animals should be walked during the cooler times of the day and, if moving some distance to a railhead, they should arrive with sufficient time to be rested and watered before loading. The maximum distances that these animals should be trekked depend on various factors such as weather, body condition, age etc., but the distance given in Table 4 should not be exceeded when trekked.

Maximum distances for trekking

| Species | One day journey | More than one day | |

| First day | Subsequent days | ||

| Cattle | 30 km | 24 km | 22 km |

| Sheep/goats | 24 km | 24 km | 16 km |

Time of the day: High environment temperatures will increase the risk of heat stress and mortality during transportation. It is important to transport animals in vehicles during the cooler mornings and evenings or even at night. This is particularly important for pigs. Heat can rapidly build up to lethal levels in a stationary vehicle. Wetting pigs with water will help keep them cool.

Duration of journey (There are recent moves in developed regions, seeking to limit the duration of livestock transports to 8 hours or less)—Where possible, journeys should be short and direct, without any stoppages. If the vehicle stops, pigs will tend to fight. Cattle and sheep/goats should not travel for more than 36 hours and should be offloaded after 24h for feed and water, if the journey is to take longer than that. Pigs should have access to frequent drinks of water during long journeys, particularly in hot and humid conditions.

Driving—Vehicles should be driven smoothly, without jerks or sudden stops. Corners should be taken slowly and gently. The second person should be in attendance to spot downer animals so that the vehicle can be stopped and the animal lifted. Train drivers should avoid “fly shunting” of trucks with livestock.

Wind chill—Wind blowing on wet animals being transported in cold weather causes a wind chill factor, where the body temperature is considerably reduced, resulting in severe stress or death